Appearance

Appendix: Ecology

Reframing Production & Consumption as Metabolic Exchange

As we first addressed in the "Overview" and will further detail in "Appendix: Architecture", Runrig makes certain architectural and design choices in order to accommodate complexity while distributing the costs incrementally over time and across a greater number of stakeholders. But it cannot achieve those ends by architecture alone, as the motto "ecology over architecture" is meant to convey. Loosely speaking, the ecology we refer to here includes the various social and biotic relations that comprise a food shed. Put another way, it is the total process undergone by the constituents of that food shed whereby their shared energy and material move throughout the system, abiding by those relations. Rather than alternately producing and consuming, as a commodities market would, an ecology always and only ever metabolizes.

For the purposes of this document, we will consider ecology by means of three approximations:

- Economic Models & Planning

- Legal Rights & Agreements

- Community Governance & Methodology

These can only serve as crude standbys for the full dynamic range of a functioning ecology, but we hope even the staunchest dollars-and-cents pragmatist can appreciate their need for attention.

Economic Models & Planning

The Core Challenge

Prior to the launch of Skywoman's MAIA Project, I argued it's not only preferable to build farm software by open and cooperative methods, but if we are sincere in our intentions to aid food sovereignty with appropriate technologies, then private startups and more traditional business models are wholly insufficient to the task:

I truly believe that the development of such resilient systems is something that can only be achieved through a radically cooperative enterprise. The data underpinning the networks of agricultural production and food distribution is so inextricably complex; it is no accident that this complexity only skyrockets when due respect and full equity is granted to every person and creature involved, as well as the land and overall ecology that contributes to feeding a community. It is a reflection of the social and cultural complexities underpinning how we eat, grow and relate to one another and our environment. I don't think there can be a just and equitable software system, capable of handling all that informational complexity, if it doesn't have social and ecological cooperation baked right into the design and methodology of the system itself.[1]

But software costs money. While we should reject the narrow view that dollars and cents are all that matter here, we still need to acknowledge that certain economic barriers must be surmounted if we wish to take any of this beyond mere theory. Specifically, software development requires compensating engineers and designers, who can otherwise fetch 6-figure salaries or more for their expertise.[2] That can drive costs quite high, and rather quickly too. As much as we seek to conserve the essential complexity of the natural systems our software hopes to model, as software complexity increases, those costs can truly explode.[3] Tremendous experience is required just to reliably estimate the final costs of an extended, complex project, let alone to keep everything on budget all the way to completion.

Being familiar with these realities from both the farmer's and the engineer's side of the table, Chris Newman addresses the complaint of a another farmer who has worked first-hand with proprietary software companies. They relate a common experience where the "solutions experts" insinuated that the complexity of the farm's operation was itself to blame for the failure of the software to meet the farm's needs. As he writes,

Software companies are not in the food business, they don't have any business telling you how to run yours, and if they do, they're deliberately attempting to throttle what works for you in order to make you work for them.[4]

One could interpret this as venture capital imposing legibility upon the social and ecological diversity of a community, to borrow an anarchist turn of phrase,[5] or what Marxists would term commodity fetishism.[6] The compulsion to simplify their operations is not meant to facilitate the existing ways a community farms and feeds itself, in accordance to its own cultural and environmental concerns; it is meant to render the labor, knowledge and matériel of that community more suitable for mass consumption and capital accumulation. Any costs associated with adapting inherently complex natural and social systems to simpler commodity forms, ready for consumption, are of course deflected onto the community itself, rather than investors.

The core challenge, however, still remains: how can diverse food communities bring their full capacities to bear upon the creation of free and appropriate technologies that meet their material needs and reflect their collective values? More to the point, how do we manage all the associated costs? While we strive to avoid further exploitation by private software platforms, we continue to live under the artificial scarcities of capitalism, so how do we manage what scarce resources we have left — amidst all other competing demands on them — to sustain communally owned software alternatives?

DRAFT NOTE

This rest of this section is still in draft. Provisional outline:

- Funding etc...

- Sliding-scale hosting & services

- Storage provisioning

Class Struggle Cooperativism

DRAFT NOTE

It may be good to refer to these principles here or elsewhere in the Runrig Plan.

In Cooperation Jackson's May 1, 2023 article, "Building Class Conscious Cooperatives", Kali Akuno lays out five "Basic Principles of Class Struggle or Class Conscious Cooperatives":

- Serving as instruments of working class self-organization, with the aim and objective of enabling the working class to own and control the fundamental means of production to enable the democratization of society and the regeneration of the earth’s ecosystems through coordinated planning to produce the use-value oriented instruments and necessities needed to improve the overall quality of life of the vast majority of the earth’s inhabitants within the ecological and material limitations of our precious planet.

- Engaging in active solidarity with other workers, worker formations, and workers self-organizing campaigns and initiatives towards the objectives of helping them become self-directed, democratic institutions committed to the socialization of production, the democratization of society, and the regeneration of the earth’s ecosystems.

- Demonstrating the principle of non-competition with and between other workers. We need to be clear that when and where we compete has to be directed against capital and its representatives to deliberately break capital’s domination over the means of production and the relations of production. On a practical level, this type of competition must entail supporting the organizing initiatives of the workers in the firms we are struggling against to help them unionize and take over the enterprise and turn it into a worker cooperative. These worker cooperatives must be willing and able to become social production enterprises willing to engage in participatory planning processes to manage the economy.

- Encouraging all existing unions, worker centers, and other worker formations to organize themselves to seize (socialize) the means of production by converting their workplaces into cooperatives or commons or social based sites of production, and support them with training materials, resource mobilization, mutual aid, consultative advice, and strategic deployment when and where necessary.

- Organizing the un and under organized sectors of the working class, who constitute the vast majority of the class, particularly in the US, into vehicles of self organization that best fit their local conditions and enable them to engage successfully in the class struggle at every progressive stage of our development and scale of deployment.

Legal Rights & Agreements

DRAFT NOTE

This section is entirely in draft and comprised mostly of notes. Provisional outline:

- Intellectual Usufruct Rights

- Service-level agreements

- Copyfair licensing

- Fiduciary obligations

- Grant/revoke proxy rights

- Broader juridico-political issues

- from the data asymmetries exploited by Big Tech to the asymmetric information leveraged by global finance

- the efficacy of contract law and legislative reform vs. direct action and more militant tactics

Main Legal Entities Constituting the Runrig System

- A data cooperative or data trust, likely incorporated as a non-profit, whose members are users of the global data provider. They can join through a service platform authorized to provision that storage on the user's behalf, or by directly provisioning space on the data provider themselves. The data coop will have legal custody of the data provider's main servers, but may contract the administration and maintenance of those servers to the worker coop (described in #2 below). It may also hold the licenses to Runrig's core software modules, trademarks, etc., though that could also be delegated to a conservancy, such as the Software Freedom Conservancy or the Commons Conservancy.

- A worker cooperative of engineers, designers and system administrators, responsible for the main data provider and core services, under contract to the data cooperative. It is also responsible for maintaining the free libraries, API's and other integrations used by the service platforms, possibly even the application software they use. They are also available on contract to develop custom, sponsored software at the request of one or several service platforms (ideally those solutions will nevertheless be contributed back to the commons and made free to all, not just the sponsoring platform). Hosting and other backend services could also be provided to the service platforms at preferred rates. In the beginning this may be more loosely structured as more of a freelancer's coop, while there may not be much in the way of significant revenues to sustain fulltime worker-owners.

- Service platform cooperatives, situated in regional foodsheds and serving more localized needs, which may vary widely in scope, purpose and membership. The specifics will be more up to the constituents of those platforms themselves, but there should be some criteria for what platforms are permitted to join the data provider and provision storage on behalf of its users. It is conceivable that they need not be a cooperative, strictly speaking, but it may be desireable place some restrictions on non-cooperative for-profit business, while also including some kind of statement of shared values in any agreements, and possibly provide discounts or other incentives to coops and non-profits.

Membership Classes

- Data Members: Individuals, farms, collectives or traditional companies who have some amount of their own data stored on the data provider, via a service platform(s) or with a direct membership account. The set of data members should be coterminous with the set of storage user accounts.

- Service Members: Platform coops and other service platforms who can join the data cooperative with the right to broker agreements with data members and provision storage for them on the data provider, granting them status of data members in the process. Note that service membership is distinct from any form of membership that entities might hold with a service platform itself, for those platforms which confer any form of membership status; such status is managed by the platforms and not with the purview of the Runrig system. It may be possible, however, for an entity to hold dual membership as both a service member and a data member. if a service member wishes to have storage on the data provider, separate from its constituent userss.

- Worker Members: Engineers, designers, etc who develop and maintain the software and underlying infrastructure. Unlike the other membership classes, these are members of separate worker cooperative, not the data cooperative.

- Community Members: Trusted supporters and advisors from the community, who may wish to participate in member assemblies and activities, but no voting rights or other privileges, so more symbolic than anything else.

Service-level Agreements

All of this necessitates that care is taken when drafting the terms of service and other service-level agreements, both between storage providers and regional platforms, and between regional platforms and individual users.

Transferral of Rights & Responsibilities

There are some potential issues when it comes to how storage and access rights, payment accounts and other privileges and obligations can be transferred between parties of various membership classes.

For instance, let's say a user joins the data coop through a service platform that pays a significant amount for that user's storage space and access on the data provider (for instance, for hi-res satellite imagery or other large media files). What happens when the user decides to leave the service platform?

There are many ways to go about this, but some possible options that could be given to the user at that time:

- Export and delete their data from the data provider.

- Transfer of payment authorization to another service or to the data coop itself, which could continue billing the user without any interruption of service or costly migrations.

- Offer free storage and access of their data in exchange for contributing it to the public domain, or participating in an anonymized public research project, with costs to the data coop offset by relevant research funding.

- Set up an application for "solidarity credits" to host a certain storage limit for a given period of time for reduced cost or free of charge.

Informational Usufruct Rights

DRAFT NOTE

These are some loose thoughts that first came up at the GOAT 2022 session on Data Policy but still need to be refined.

There is a prevalent yet false impression about data, that it is a form of intellectual property, and that ownership or certain legal entitlements pertain to data the same way they do to creative works, software and real property. Feist v Rural Telephone, GDPR, etc, etc.

Can intellectual property rights be reframed as informational usufruct rights? Such rights can then be governed in terms of who is granted access (usus) to that information, which can constitute either a creative work or data set, as well as its derivatives (fructus); however, exclusive rights to alienation (abusus) will be rejected, except in the case of personal data as defined by the GDPR. Care should also be given to ensure that all rightsholders enjoy an equal capability to make full use of such information as they please.

Ejidos digitales

...like water rights, but for the flow of data; or collective land management, but for network infrastructure and compute resources.

Data Cooperatives & Fiduciary Obligations

DRAFT NOTE

These are taken straight from an earlier set of personal notes, and so need to be rewritten entirely. And while the legal aspect of fiduciary agreements should be discussed here, the specifics of data coop governance should probably wait until the next section.

In an article from Coop Exchange about data coops, they describe the Driver's Seat Cooperative's mission:

Drivers Seat Data Cooperative allows drivers using platforms like Uber or Lyft to track their driving and pay to figure out the optimal times to make money based on their schedule, where they should drive when it is slow, etc. They can choose to share the data with city agencies to help with transportation planning. The drivers own the cooperative and it enables them to get more money for work they are already doing.

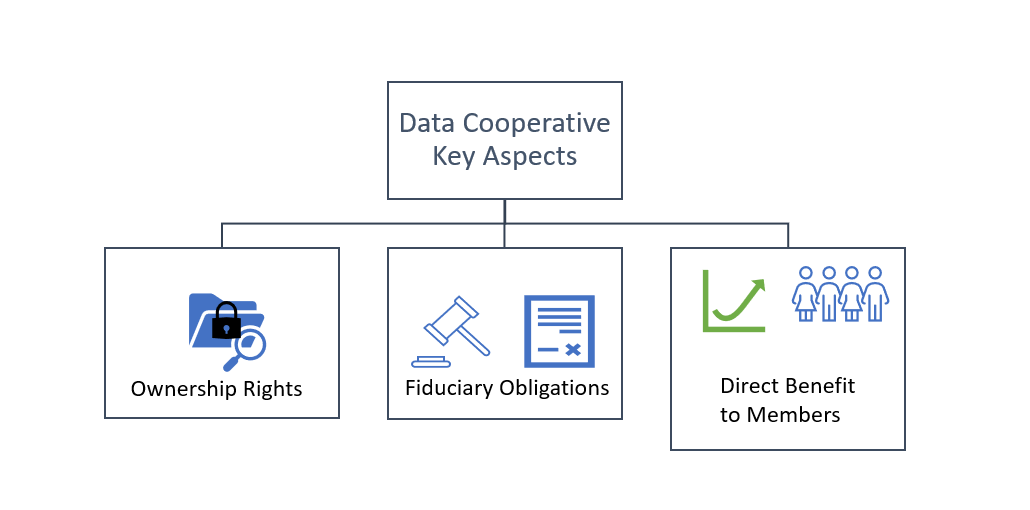

This got me to think again about the whole concept, especially as it relates to Regen Farmers Mutual. Looking on the Wikipedia page, it had a great little diagram:

Follwing some references from the same Wikipedia article, I found a couple of good scholarly articles. Chief among them, "Data Cooperatives: Towards a Foundation for Decentralized Personal Data Management" by Thomas Hardjono and Alex Pentland is most pertinent to the fiduciary obligations of data coops specifically, as the abstract indicates:

Follwing some references from the same Wikipedia article, I found a couple of good scholarly articles. Chief among them, "Data Cooperatives: Towards a Foundation for Decentralized Personal Data Management" by Thomas Hardjono and Alex Pentland is most pertinent to the fiduciary obligations of data coops specifically, as the abstract indicates:

Data cooperatives with fiduciary obligations to members provide a promising direction for the empowerment of individuals through their own personal data. A data cooperative can manage, curate and protect access to the personal data of citizen members. Furthermore, the data cooperative can run internal analytics in order to obtain insights regarding the well-being of its members. Armed with these insights, the data cooperative would be in a good position to negotiate better services and discounts for its members. Credit Unions and similar institutions can provide a suitable realization of data cooperatives.

The article even goes into some specifics on the technical architecture and how to use the MIT "Open Algorithms" paradigm (abbreviated as OPAL) in the implementation of data coops. The authors, together with Alexander Lipton, are also the authors of Building the New Economy: Data as Capital. In this article, however, they give a concise description of 3 "key aspects" of data coops, which I believe is the source of the diagram above:

Individual members own and control their personal data: The individual as a member of the data cooperative has unambiguous legal ownership of (the copies of) their data. Each member can collect copies of their data through various means, either automatically using electronic means (e.g. passive data-traffic copying software on their devices) or by manually uploading data files to the cooperative. This data is collected into the member’s personal data store (PDS) [3]. The member is able to add, subtract or remove data from their personal data store, and even suspend access to their data store. A member may posses multiple personal data repositories.

The member has the option to maintain their personal data store at the cooperative, or host it elsewhere (e.g. private data server, cloud provider, etc). In the case where the member chooses to host the personal data store at the cooperative, the cooperative has the task of protecting the data (e.g. encryption for data loss prevention) and optionally curating the data sets for the benefit of the member (e.g. placing into common format, providing informative graphical reporting, etc.).

Fiduciary obligations to members: The data cooperative has a legal fiduciary obligation first and foremost to its members. The organization is member-owned and member-run, and it must be governed by rules (bylaws) agreed to by all the members.

A key part of this governance rules is to establish clear policies regarding the usage or access to data belonging to its members. These policies have direct influence on the work-flow of data access within the cooperative’s infrastructure, which in turn has impact on how data privacy is enforced within the organization.

Direct benefit to members: The goal of the data cooperative is to benefit its members first and foremost. The goal is not to “monetize” their data, but instead to perform on-going analytics to understand better the needs of the members and to share insights among the members.

The references section is also a goldmine, with several other articles by the same authors. Also among those references is a pretty good article from UC Davis on the legal aspects of information fiduciaries in general, coops or not, titled "Information Fiduciaries and the First Amendment".

Community Governance & Methodology

DRAFT NOTE

This is just a placeholder for a section that needs drafting. Provisional outline:

- Data cooperatives (split this out from the fiduciary discussion above?)

- Distribution of voting shares

- Standards & Tools (might delete)

Follow-up on this research on data governance by UK non-profit Nesta, via Muldoon:

- Mulgan, Geoff and Vincent Straub. "The new ecosystem of trust", Nesta, 21 February 2019.

- Borkin, Simon. "Platform co-operatives – solving the capital conundrum", Nesta, February 2019.

- Bass, Theo and Rosalyn Old, "Common Knowledge: Citizen-Led Data Governance for Better Cities", Nesta, January 2020.

Standards and Tools

DRAFT NOTE

Much of this section seems like a poorly focused rehashing of the "Economic Challenges" above. Most of it can probably be scrapped, but see what portions actually pertain to governance & methodology and could be salvaged.

We've come to believe what we're told about data standards and shared ontologies: that they are great in theory, but in the real world things are too complex and you either end up having a standard that's too specific and opinionated that it doesn't work for everyone, or too broad and generalized that it's just not very useful. The Semantic Web itself has endured a great deal of criticism along these lines over it's 20-year history.

But the unspoken assumption here is that those standards have to survive "trial by market", where the kind of close coordination required to produce and maintain a practicable, living standard is all but prohibited by the profit-seeking, competitive demands of the market. Even as proprietary software giants like Microsoft and Oracle become cozier with open source technologies and a general appreciation of the "commons" pervades the industry, control of the actual data and services generated by those open source tools remains heavily restricted and privatized. After all, without the privatized control of some utility or the enclosure of some asset, where would the capital accumulation come from?

Attempts to take back ownership and control of "Software-as-a-Service" have largely struggled, I would argue, because we've sought too narrowly to redistribute those rights piecemeal to individual users, rather than seeking common ownership. Certainly, there are great benefits to individual control in many contexts, but we handicap our projects by limiting ourselves to those alternatives exclusively. Taken to the extreme, this would necessitate everyone have their own server rack in the garage (or at least a Raspberry Pi in the closet), each of us rolling our own servers independently from one another.

My fear, however, is that if we're too predisposed to self-hosting, we will needlessly alienate people who may not want to use a particular piece of software or hardware, but may wish to participate in the social and economic activities that such software and hardware facilitate. We would do well to regard Ivan Illich's criteria for "convivial" tools:

Tools foster conviviality to the extent to which they can be easily used, by anybody, as often or as seldom as desired, for the accomplishment of a purpose chosen by the user. The use of such tools by one person does not restrain another from using them equally. They do not require previous certification of the user. Their existence does not impose any obligation to use them. They allow the user to express his meaning in action. (22)

While promising new paradigms like software "appliances"[7] might eventually offer the option of plug-and-play personal servers, achieving both autonomous and ubiquitous computing in the same stroke, they would still leave critical issues unaddressed. The data and computing capabilities of several billion humans are today at the whim of just a few dozen technocratic billionaires. Any serious challenge to these proprietary platforms, and all the coercive force at their disposal, must come from a base of organized, community-driven political power, built around shared resources. Now is not the time to retreat into isolation, each of us behind our own firewall.

Common ownership of our platforms is a far more effective means towards that end, but also an end in itself...

References

Gaehring, Jamie. "Toward a Platform Cooperative for Food Sovereignty". August 05, 2022. ↩︎

Bound up in the problem of software costs is the ill-founded distinction between skilled and unskilled labor, and it must be addressed when considering an industry like agriculture where wages are routinely stolen and rarely meet the standard of a true living wage. We should aim to counteract such tendencies as much as possible through transparent pay scales, explicit limits on compensation, and other measures, even if that means less competitive salary offerings for technical workers. However, discretion should always be applied here. Tech workers will and ought to be mindful of the opportunity costs associated with accepting a lower paying position, even if they see the higher purpose, while also weighing that with any educational debt they may have accrued, or how their salary history may effect future offerings. It should never be incumbent upon these workers alone to fix the societal error of assigning higher absolute skill-level to any one form of labor over another. ↩︎

Since at least 1986, with the publication of Fred Brooks' paper, "No Silver Bullet — Essence and Accidents of Software Engineering", engineers and designers have been trained to distinguish two forms of complexity: essential and accidental. Essential complexity is inherent to the problem at-hand, what is called the domain or business logic; it exists prior to the introduction of the software tool and cannot be reduced by engineering alone. Accidental complexity, on the other hand, derives from the use of software in its own right, like the complexity of handling network latencies or multithreading; it may be unavoidable to some degree, but it is the only form of complexity that the software engineer can rightly try to eliminate. As a rule of thumb, the greater the complexity of the software, in either form, the greater its costs in both time and money. While it may be appropriate for the domain experts (ie, the business managers, workers and end users of the software) to reduce the essential complexity of the real system the software represents, any attempt by the software developers to forgo aspects of essential complexity can only represent a flaw of omission in their modeling. ↩︎

Newman, Chris. "Choosing Software: The Case for Using ERP/CRM/SCM to Scale Farms". Jan 3, 2023. ↩︎

Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. ↩︎

James Muldoon and others extend Marx's concept to what they call data commodity fetishism, which he defines as "the perception of certain digital relationships between people (especially for communication and exchange) as having their value based not on the social relationships themselves but on the data they produce." See Muldoon, Platform Socialism, p. 18. ↩︎

Congden, Lee. "What is a Software Appliance?"The Red Hat Blog. Jan 25, 2008. ↩︎